After Barbie's Release, Consumers Requested a Male Counterpart. There Was Only One Issue.

- HOME

- ENTERTAINMENT

- After Barbie's Release, Consumers Requested a Male Counterpart. There Was Only One Issue.

- Last update: 2 hours ago

- 2 min read

- 343 Views

- ENTERTAINMENT

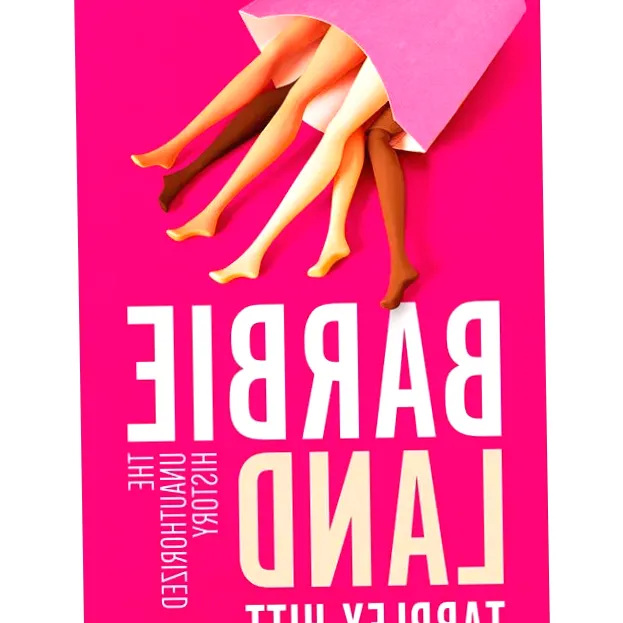

In 1960, during Barbies triumphant first year, Mattel founders Ruth and Elliot Handler convened a meeting that brought together the companys marketing team and external advertising experts. Among the attendees was Ernest Dichter, a prominent New York-based psychologist and marketing strategist known for his Freudian approach to consumer behavior.

The discussion centered on a delicate and contentious issue: the design of Barbies prospective male companion, Ken. As Mattel had grown into a publicly traded company with a vast audience of children and fans, the Handlers faced mounting pressure from their consumer base. Girls were writing letters to Barbie in staggering numbers, prompting Mattel to create newsletters, and eventually, the Barbie Fan Club, which became the second-largest organization for girls worldwide.

With the fan clubs growth came repeated requests for a boy doll. The idea of a boy doll was unconventionaltoy executives believed girls did not desire male dolls, and past attempts by others had largely failed. Nevertheless, Mattels consumers demanded a companion for Barbie, leading to the decision to develop Ken.

The creation of Ken raised challenging questions about how his physique should be represented. Barbie had already been anatomically suggestive, and Ruth felt that Ken should have a subtle hint of male anatomy. Her proposal was modest, seeking only a slight indication rather than explicit detail. The companys sculptors, designers, and executives debated the idea extensively, producing multiple prototypes ranging from minimal to more pronounced forms. Ultimately, Ruth and fashion designer Charlotte Johnson selected a middle-ground design that appeared aesthetically balanced.

However, practical manufacturing concerns overruled these plans. When Kens molds were sent to Japan, an engineering supervisor determined that adding shorts and a slight bulge was too labor-intensive and costly, resulting in Ken being produced smooth and without any anatomical features.

The final version of Ken, revealed at the 1961 Toy Fair, lacked the subtle details Ruth had advocated. Despite her frustration, this compromise highlighted the tension between artistic vision, consumer expectations, and production realities. Kens development became an early example of Mattel responding to public demand, setting the stage for ongoing negotiations between brand ambition, consumer input, and commercial practicality.

Author: Sophia Brooks

Share

The Impact of Convenience on Black Communities: The Price of Plastics

1 minutes ago 5 min read ENTERTAINMENT

Rihanna Rocks Dramatic Balenciaga Look with A$AP Rocky at Gotham Awards 2025

1 minutes ago 2 min read ENTERTAINMENT

Channing Tatum Gets 'Emotional' Over New Movie Leading to Real Life Family Reunion for Roofer

3 minutes ago 2 min read ENTERTAINMENT

Younger generations choose environmentally friendly options over imported fresh flowers

3 minutes ago 3 min read ENTERTAINMENT

'People We Meet on Vacation' Trailer: Tom Blyth and Emily Bader Discuss Friendship Boundaries

4 minutes ago 2 min read ENTERTAINMENT

It's Beneficial for Us to Sing as We are Naturally Inclined to Do so

4 minutes ago 4 min read ENTERTAINMENT

SNL cold open mocks Trump for appearing to doze off during meetings — and suggests he was dreaming of Mamdani

4 minutes ago 2 min read ENTERTAINMENT

Publisher of 'Franklin the Turtle' criticizes Hegseth for 'violent' use of character in meme

5 minutes ago 2 min read ENTERTAINMENT

New and Streaming on Netflix in December: Check Out the Latest Releases

6 minutes ago 3 min read ENTERTAINMENT

Check out the latest additions to Hulu's streaming lineup in December

6 minutes ago 2 min read ENTERTAINMENT