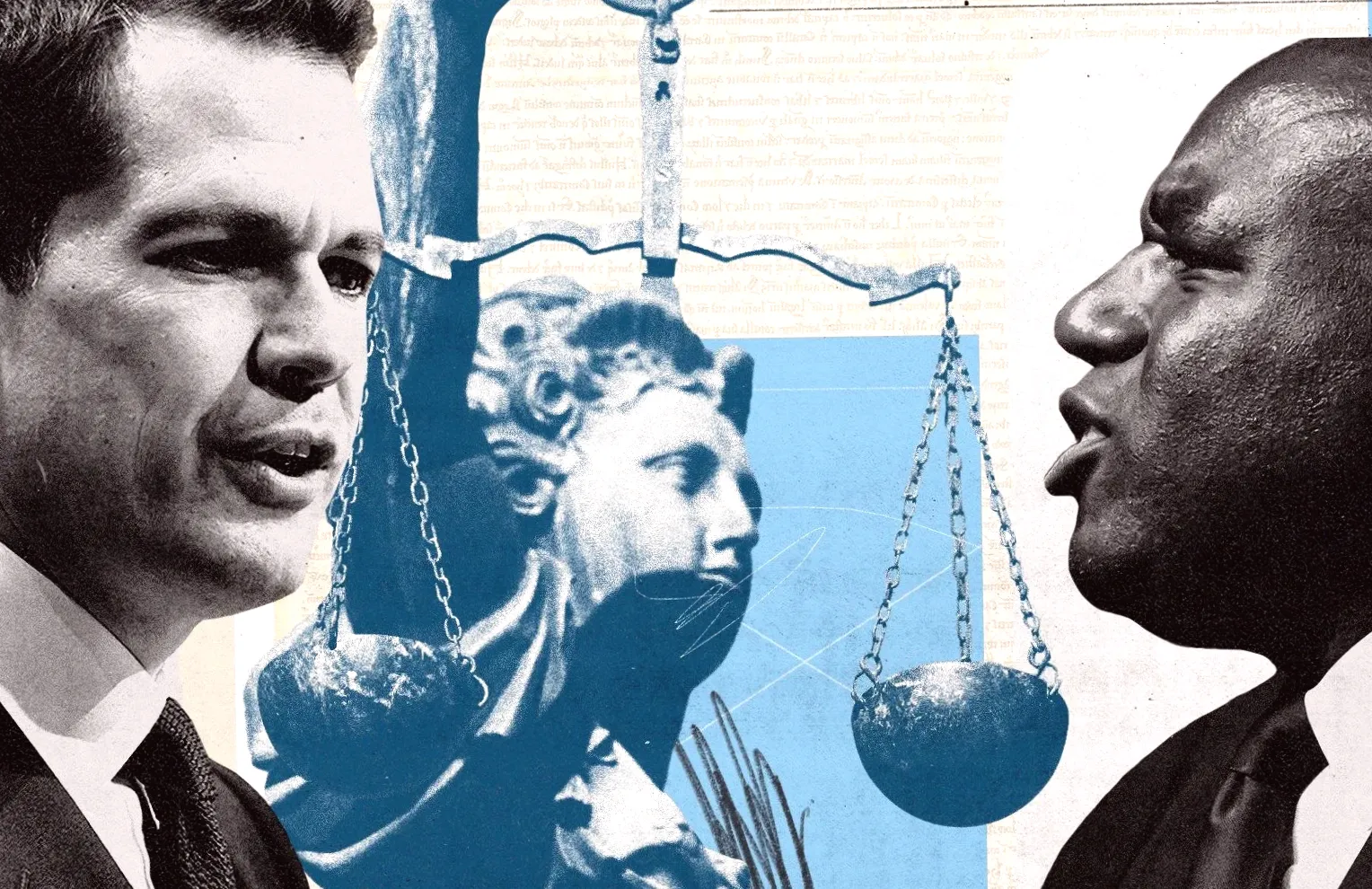

English identity is being challenged by threats to the jury trial system

- Last update: 3 hours ago

- 3 min read

- 151 Views

- WORLD

England, with its long and stable history largely free from civil conflict, has developed a way of life deeply rooted in tradition. Many of these traditions, including trial by jury, have been preserved and shaped over centuries, occasionally reinforced by legislation. The jury system, which has existed in some form for over a thousand years, can trace its origins back to the Danish invasions.

This method of justice, later refined by Henry II after the Norman Conquest, initially addressed land disputes before expanding to criminal cases. In 1215, the Magna Carta cemented the right to trial by jury, stating that no free person could be punished except by the judgment of their peers or the law of the land. By the 14th century, twelve-member juries were customary in administering English law.

Over time, the jury system has evolved. Women have participated since 1920, and property qualifications for jurors were removed in 1974. Modern jurors no longer investigate cases themselves; the police and Crown Prosecution Service handle investigations, though shortcomings in these institutions have introduced systemic flaws unrelated to juries.

Historical challenges have reinforced jury independence. In 1670, an Old Bailey judge attempted to coerce a jury in a case involving William Penn. The Lord Chief Justice intervened, emphasizing that jurors must retain independent judgment, a principle that has protected the system ever since.

Today, most criminal cases are resolved in magistrates courts without a jury, accounting for around 90% of prosecutions. Only serious offences, such as murder or rape, typically involve juries, though even then, only a small percentage of trials are contested. Lesser offenders can still request a jury trial, a right occasionally exploited for publicity but essential to uphold justice principles.

Recent proposals suggest restricting jury trials to offences with sentences of three years or more. This would also shift certain cases to magistrates courts or a new judge-only Crown Court. Critics argue this threatens a centuries-old tradition and risks undermining public trust in the justice system. Extending magistrates sentencing powers to two years without a jury has been described as "decidedly un-English."

Justice Secretary David Lammy defends these reforms as necessary to reduce court backlogs, which could grow beyond 100,000 cases by 2029. Opponents, including legal organizations and some MPs, contend that such measures only address symptoms rather than the root causes of delays, such as insufficient judges, lawyers, and court resources. Past pandemic closures worsened the backlog, but experts highlight a broader "productivity crisis" in the court system.

Research shows Crown Court trial hours have not dramatically increased in recent years, indicating that limiting jury trials would have minimal effect on efficiency. Many delays stem from infrastructure issues, inadequate staffing, and mishandled case management, not the jury system itself. Courts also have numerous underused courtrooms due to resource constraints.

The risk of reducing jury trials extends beyond efficiency. Removing juries in traditional cases could erode public confidence in fairness, potentially creating perceptions of class-based justice. The jury remains a vital democratic mechanism, involving citizens directly in the administration of justice and ensuring decisions are not confined to an elite.

While not flawless, the jury system is a cornerstone of English values, reflecting centuries of civic trust and participation. Attempts to curtail it, driven by bureaucratic expediency or technocratic reasoning, threaten a foundational element of the legal system. Public sentiment and historical precedent strongly favor retaining jury trials in serious criminal cases, safeguarding both liberty and the rule of law.

Author: Olivia Parker